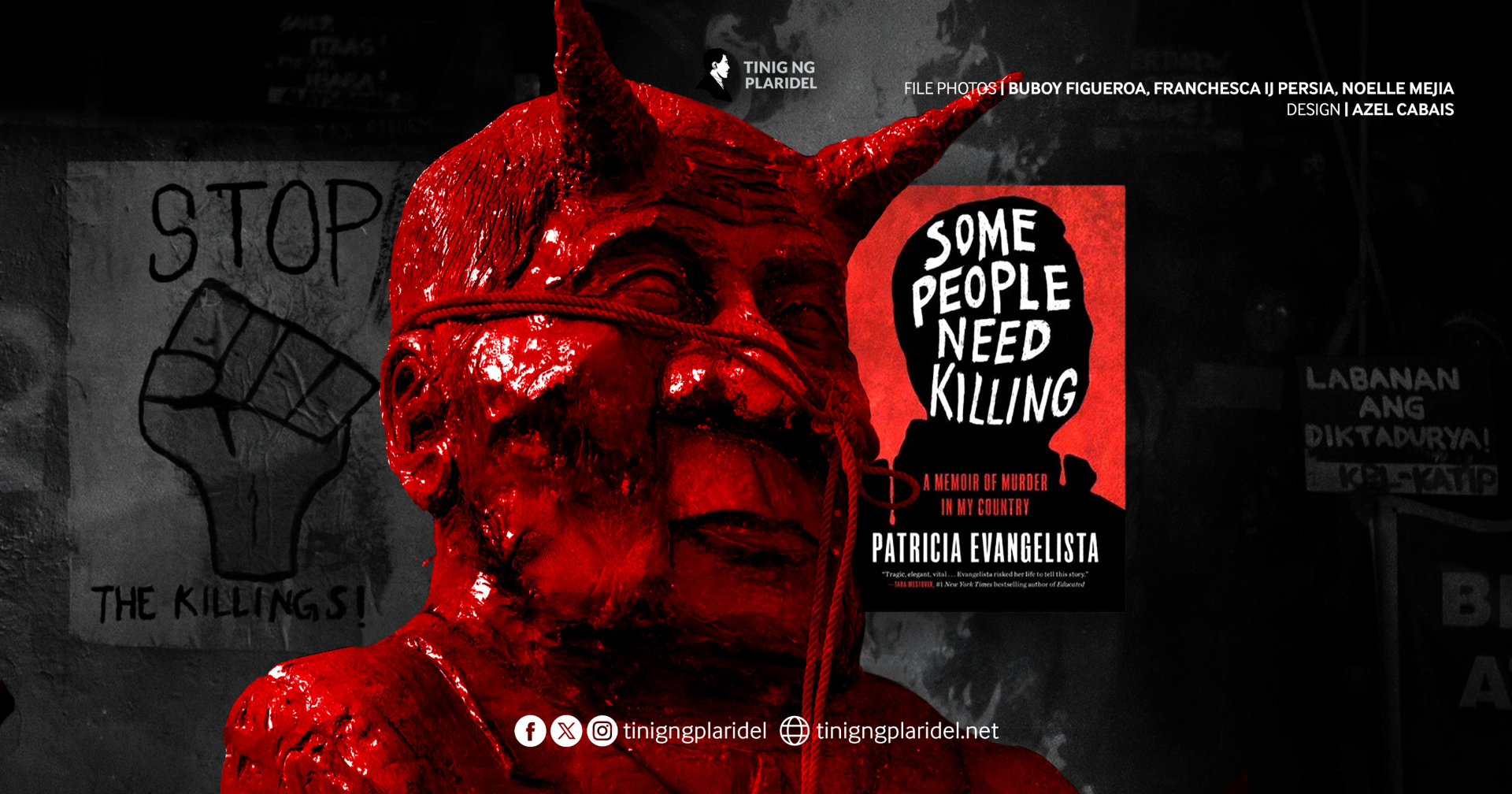

The curtains open with a gunshot. A lifeless body falls to the ground. A pistol and packets of crystal meth are then planted near the victim, alongside a cardboard sign bearing the words: Pusher, Huwag Tularan. The killer exits the stage and prepares for the next scene.

The play’s setting is the Philippines. The producer lives in a palace and goes by the name Rodrigo Duterte. The man who, among all the possible roles, decided he wanted to play God.

In “Some People Need Killing,” Patricia Evangelista pieced together years of her trauma reportage to furnish what single-piece stories could only try to show— the bigger picture of Duterte’s war on drugs now conveniently packaged in a book. For the palm of our hands.

In true journalistic fashion, the overall structure of Evangelista’s book also bears a striking resemblance to news articles.

The first chapter seemed like the lead, hooking the readers with heartbreaking stories of children exposed to the brutal drug war. Some were left behind after watching their parents’ execution, while some did not survive at all.

The story then took a step back for the nutgraf to detail Duterte’s rise to power. It was imperative to show that the killings did not start on June 30, 2016, the day the notorious former president ascended to Malacañang.

The long trail of blood dripping from Duterte’s hands actually traces back to his political debut in Davao City, to the death squads that allegedly operated under his orders, to his law school where he admittedly shot a fraternity brother, and to 1987 when vigilante groups were formed against communists—an initiative reportedly supported by no other than Corazon Aquino and the United States regime.

Evangelista’s journalistic roots were also most notable in her scrutiny of language. A reporter herself, she showed how important it was to be precise in her own choice of words, and by extension, in her sources’ use of such.

The book recognized that beyond the string of killings on the ground, there exists a battle of words in how the truth is deliberately concealed— if not fabricated— in official state reports.

Take for example the time when the police started using the word “neutralize” to refer to the act of gunning down their targets.

“Each of these men is dead, but in the official reports of all these cases, none of them were referred to in the narrative of events as killed,” the book narrates.

This euphemism masked by posh and formal English enabled the police to hide their intent to kill. It inherently presumes that any target is a threat, whether true or not.

They wanted us to buy their brazen attempt to establish and control a dominant narrative. That everyone nanlaban and therefore deserved to die, whether they were an innocent child, a harmless student who had exams the next day, or even a struggling epileptic running an errand.

It becomes clear from here that Duterte’s notorious campaign was based on the exact blueprint of information disorder that elected him to power. That if you repeat a lie, rhetoric or an empty promise at least a hundred times, it won’t be long enough for them to appear real.

I was a lanky, high school student when I first knew of Oplan Tokhang in our barangay. I was lying on the upper bunk of our bed when a loud thud momentarily froze the noise in the air.

I did not know it was a gunshot back then because it was the first time I had heard one in my life. It was the following shrieks and screams that confirmed my assumption.

I asked my father what he remembered about that day, but he immediately turned down my question. I threw the same question to my mother at a different time, and she said multiple vigilantes wearing black were seen fleeing the scene using motorcycles. How many, I asked. Marami, she plainly said, as if hinting for me to stop.

In a whisper, I then asked if the victim—a parlorista who works a street across our old house—was indeed a drug user. She said yes, but only based on hearsay when it became the talk of the town the next day.

The last question I had was for myself: how many victims were truly drug suspects before being killed, and how many were just labeled as such after the trigger was already pulled?

Under Duterte, drug use became a regular justification for killing suspected users. As if the moment you consume or carry an illegal substance, you forfeit your right to be human, relegated to the class of pests and insects of society.

I searched the internet for an article about the extrajudicial killing in our barangay but failed to see any. Some people, I realized, don’t even make it to the news to get their names cemented as fact.

This is where the charm of Evangelista’s book lies. It was a story that had to be written and engraved in our history. Had to. Not just urgency but a necessity. A must. For us to remember and never forget.

Moreover, the book was not just a story of the dead. It was a story of those who were left behind. It traverses not just the lives that were lost but also the lives of those who continue not in spite of, but because of the loss.

Like most tragedies, Some People Need Killing ended with a story of regret. People who voted for and applauded Duterte are now choosing to undo their mistakes and help in whatever way they can.

We cannot bring the dead back, but we can at least move forward and join the sea of voices rallying for accountability and justice.

If regret is the emotion that could rally our people in the direction of change, then let everyone grieve in contrition. For they, too, are just victims of a lie, rhetoric and empty promises repeated at least a hundred times.

The people gave Duterte power through an election filled with lies and deceit. Now is the time for the same people to take it back.