TW: This article contains mentions of violence.

There are cases where, despite our best efforts and wishes, history seems to move on. Not because of any moral failing or withheld duty, but simply because of the passage of time.

When director JL Burgos was in a conversation with a young activist during one of the rallies they attended, he mentioned his brother, Jonas Burgos—a peasant rights’ advocate who went missing in 2007 after being abducted in Ever Gotesco Mall by the military.

The young activist replied that they did not know of him, much to the director’s surprise.

Before entering Cine Adarna, the reception area was filled with youth: students from different colleges and universities, some incentivized to watch the film for a GE class. Some were curious folk, middle-aged people that may have known of the abduction, who may have been interested to see JL’s work.

But there were a few who sat by the corner and offered their seats to the newcomers before we went inside.

We had learned then that those were the families of the desaparecidos—a term used to describe people who “disappeared,” or forcefully taken by state forces and subjected to indefinite detention and torture.

It was first used in the 1970s, when cases of forced disappearance began to emerge in Latin America. During the same period, the Philippines was under Martial Law imposed by the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

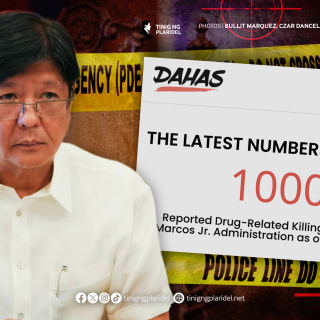

To date, there are still 1,915 missing persons out of the total 2,586 enforced disappearances recorded in the Marcos Sr. regime. More than five decades later, a total of 38 desaparecidos have been tallied under his son’s administration, with 15 of them yet to surface.

Alipato at Muog is a documentary film that describes the events that had transpired for the Burgos family since the abduction of Jonas. It tells their family’s relentless pursuit for an answer—how they went from one military camp to another, attended countless hearings, visited several police stations—trying to find evidence for his abduction or anything that might help them to resurface Jonas, whether alive or not.

But describing the film as that would only tell half the story. In truth, the director and his family searched high and low for Jonas, opening up a perspective unbeknownst to them about what he was doing. Among a collective of farmers in an undisclosed location, Jonas had taught them that they were entitled to the land that they tilled—and worked tirelessly for those farmers to receive that land for themselves.

The film creates a portrait of Jonas and how he was as an organizer, as a friend, as a brother, as a family man. In that same light, however, the film had more to say about the sinister machinations that had plagued their family’s search in the first place.

Despite credible evidence submitted to the Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, and the Commission on Human Rights that there were elements of military involvement in Jonas’ abduction, military officials were quick to deny these findings. They tagged Jonas as a “high-ranking communist leader” and pinned the blame on the New Peoples’ Army for his abduction.

During instances when their mother Edith Burgos, JL, and their lawyer sought meetings with decorated officers of the military, they were met with indifference at best, and blind rage at worst. The three recalled a time when a high-ranking military officer rammed the side of their car after a particularly tense meeting inside the military camp.

It shows that even with the clamor of support towards those who were wrongfully deprived of their human rights, there remain powerful figures who wield power with impunity, untouched by the cries for justice.

Because this film does not merely focus on the Burgos’ search for truth and justice for Jonas. It tackles the emergence of the desaparecidos—those who had lived through the disparaging events of a “golden” era that spilled blood and stifled voices.

To the families of the desaparecidos, the anguish was a relentless shadow, a pain that would “never go away” as they grieve for a life without a body to bury. In the director’s narration, he didn’t know whether this was good or bad; he kept hoping that Jonas would still be alive. There was no certainty to be had.

As the lights of Cine Adarna went back on again, there were faint sounds of sniffling across the theater. It seems as though the youth who were lively and conversational before the viewing had become silent.

I looked around and saw that I was beside another family of desaparecidos. A sharp pang pierced my chest, as it did for everyone else in the theater—a silent echo of our collective grief that hung heavy in the air.

There was something to be said about being in proximity with those who experience what we had just witnessed. Do we stay polite and smile at them? Do we abandon pleasantries and approach them for an embrace? How can we contend with the fact that our own government allowed the disappearance of their beloved family?

There are films that need not be created; but there are also those who shouldn’t have been made in the first place. Alipato at Muog marks its existence with murky beginnings and an even more uncertain “end.” A film borne out of necessity: a need for symbolic closure, a need for definitive answers.

During the talkback, JL mentioned that the film took so long to release because he was “looking for a happy ending.”

They started filming in 2007—mainly for evidence, he noted, but soon became a project he sought to accomplish. JL shared that the editing of this film, which took almost a year, was “very difficult” since the “trauma” of searching for Jonas was coming back to him.

The movie was awarded with Cinemalaya’s 2024 Special Jury Prize for full-length film.

Originally, Alipato at Muog was given an X rating by the Movie and Television Review Classification Board (MTRCB), citing that it “undermined the faith and confidence of the people in their government or duly-constituted authorities.” It was then reclassified to a R-16 rating after a secondary review.

The director also noted that the film was initially classified as such because the MTRCB did not want to earn the ire of Eduardo Año—former military general-turned-National Security Advisor under Marcos Jr. Año had been implicated by the film to be one of the military elements involved in the abduction of Jonas.

Yet these trials did not seem to plague JL’s insistence in “speaking truth to power.” In the end, it was not a matter of courage, but a matter of love that made him share their experience through film.

“Hindi kami matapang […] pero mahal ko ang pamilya ko,” he shared.

In JL’s view, had he not shared this with the world, had he stopped trying to search for Jonas despite the threats they were receiving, he would have felt “complicit of the sins that’s being committed.”

“It is our [family’s] responsibility to introduce Jonas to activists,” he said.

We walked out of Cine Adarna holding our chests, tissues at hand. Frightened by the country we live in, yes, but invigorated with the inspiration that the Burgos family maintains despite it all.