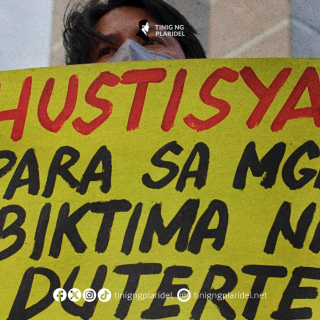

Filipino journalists continue to grapple with violence, killing, and impunity 15 years after the Ampatuan Massacre, the “single deadliest event” for journalists.

The massacre took 58 lives, 32 of which were media workers who just joined the caravan of local politician Esmael Mangudadatu. They were on their way to file Mangudadatu’s certificate of candidacy on Nov. 23, 2009, challenging the eight-year rule of the Ampatuan clan in Datu Unsay, Maguindanao.

It took a decade for the Ampatuan brothers—Andal Jr., Zaldy, and Anwar Sr.—to be convicted as the primary orchestrators of the massacre. They were sentenced to reclusion perpetua, equivalent to 40 years in prison without eligibility for parole or the possibility of serving their sentence in the community.

Amnesty International described the conviction of the Ampatuan brothers as a “delayed justice” to the families’ victims. Meanwhile, the International Federation of Journalists only considered the decision “partial justice” since 76 of the accused remained at large.

Until now, journalists contend with persistent threats to safety and security. Commentator and well-known Duterte critic Percy Lapid Mabasa was shot dead on his way home in October 2022, just three months after President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. began his term.

As of press writing, five journalists have been killed under the Marcos administration, with radio anchor Maria Vilma Rodriguez being the latest when “unknown assailants” shot her near her home in Zamboanga City on Oct. 22.

A day after the crime scene, the suspect was detained and kept anonymous in light of the ongoing investigation. No updates on the case have been publicly announced as of press time.

In the 2024 Global Impunity Index, the Philippines ranked 9th with 18 unsolved murders while Haiti tops the list. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) said the country has consistently logged unsolved murder cases of journalists almost every year since 1992.

The Philippines has been appearing in the ranking since 2008 and has frequently secured the first or second spot.

The climate for media workers under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. “worsened” despite his pledge to uphold press freedom, according to a statement released in July 2023 by the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

Chilling effect

Philippine journalists also reel with state-sponsored harassment and arrests, as NUJP recorded 84 attacks on media workers between June 30, 2022 and July 22, 2023.

Leyte-based community radio broadcaster Frenchie Mae Cumpio was detained on trumped-up charges of illegal firearm protection and terrorist financing in February 2020. She was only able to take the witness stand on Nov. 11, four years after state forces stormed her residence in the wee hours of the morning.

Should Cumpio be convicted of the charges pressed against her, she may face imprisonment of up to 40 years in prison.

The National Union of Journalists, together with other local media organizations and advocates, called for her immediate release, describing the charges filed against Cumpio as “exaggerated” and a deliberate act to red-tag journalists and link them to the armed communists.

The persistent harassment of government authorities sends chilling effects to newsrooms, according to a report from Human Rights Watch.

Lack of Legal Protection

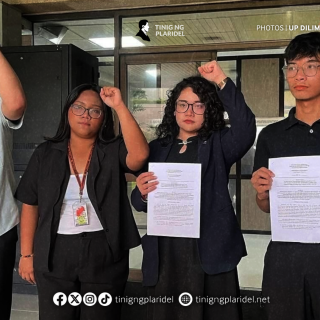

Aside from attacks, journalists also suffer from low wages and contractualization, according to the Union of Journalists of the Philippines UP Diliman (UJP-UPD).

To protect media workers from labor exploitation, Marcos signed Republic Act 11996 or the Eddie Garcia Law, which regulates work hours, wages, benefits, welfare services, and basic necessities of media workers, regardless of their position.

Named after veteran actor Eddie Garcia, who passed away in 2019 due to an accident while filming a TV series, the law aims to enjoin media companies to protect the health and safety of media workers. It requires media networks to adhere to existing regulations, such as the Labor Code of the Philippines, and imposes penalties of up to half a million pesos for non-compliance.

While the law offers a safety net for media workers, it does not address threats faced by media practitioners, such as red-tagging, harassment, or violence from both state and private actors.

“The law is a positive step in regulating the film and TV industry that urgently needs it. Aside from the law, film and TV workers must use this opportunity to air their experiences, further study the conditions in the industry, and strive to unite and organize fellow film and TV workers,” said Eyes on Set Network, a watchdog group launched last September 11 to ensure compliance to the Eddie Garcia Law.